FYI, Caught Green Handed is a newsletter interrogating the relationship between fashion and green capitalism. If you enjoy this post, subscribe to get more hot, anti-greenwashed takes directly in your inbox 🫶

Earlier this month, the UK and EU creative director of PrettyLittleThing, Molly-Mae Hauge, announced “something that no one's gonna expect”. The something in question? A resale app that’s set to rival the likes of Depop and eBay.

The UK-only app is expected to be launched in May, before rolling out to the US by the end of the year. Here, users can sell pre-loved clothing from any fashion brand. Where the app differs from conventional resale platforms is in its ability to sync up with the user’s PrettlyLittleThing order history. Customers simply select the PLT item they want to sell on and a listing will be automatically created, complete with the original ecommerce images and description.

Molly-Mae anticipates that the move “will disrupt the fashion industry, as people aren’t going to expect this from us”, but this really isn’t that novel. Levi’s, New Look, H&M Group. Urban Outfitters and ASOS all have their own resale initiatives, with the latter dating back to 2010. PLT’s foray into the secondhand sector, then, is unlikely to disrupt an already saturated market.

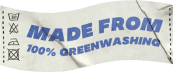

Maybe the app will be disruptive in its impact, greenifying PLT’s operations and scrubbing clean its filthy record of environmental and social wrongs. The platform is certainly framed as “encouraging sustainability” - an angle that was lapped up by the press, with one headline equating the move with “going green”. According to the article, PLT’s poor environmental performance is “all about to change”.

Except it’s not. PrettyLittleThing isn’t pivoting to a resale model. It isn’t taking responsibility for the entire lifespan of its garments or dramatically scaling back production. The brand is simply diversifying its revenue stream.

Money. That’s the real reason fast fashion wants to get into resale, and it’s easy to see why. The secondhand clothing market has exploded, growing at a rate that’s 11 times faster than traditional retail. By 2030, the secondhand clothing sector will be worth an estimated $84 billion - more than double the fast fashion industry’s worth.

PrettyLittleThing will be up against Depop, the prime destination for PLT clothes. Currently, there are more than 401,00 search results for “pretty little thing”, and over 280,000 for “plt” on the app. Last summer, PrettyLittleThing was the fifth most listed brand on Depop.

Capitalising on resale, then, isn’t part of some noble mission to heal the planet. It’s a calculated move to mitigate the competitive threat of resale and convert Depop’s active user base - 90% of which are under 26 - to its own platform. It’s ultimately an opportunity to duplicate revenue on the same item of clothing, clothing PLT used to lose sight of the second it was sold.

If we can get past the fact that this is nothing more than a money making exercise, should we celebrate its sustainable potential? Hell no. Beyond the financial incentive, it makes little sense for a disposable fashion brand to create a secondhand platform.

For circularity to work, garments need to be responsibly made, of high quality, and marketed slowly. So, how do you disentangle the circularity messaging of resale with the reality of the fast fashion linear model?! PrettyLittleThing produces flimsy, temporarily trendy clothes that aren’t designed to be worn tens of times, let alone be passed from wardrobe to wardrobe. Its marketing tactics are fine tuned to encourage frequent and impulsive purchases, while its influencer base feed into a widespread anti-outfit repeating mentality.

PrettyLittleThing “wants people to love these garments and wear them constantly”, but that’s at odds with its actions. Today, there are 98,512 unworn items of PLT-branded clothing listed on Depop. These regretful purchases are partly the fault of a brand that encourages you to hastily buy into trends, and whose sizing and quality is inconsistent. PrettyLittleThing is now banking on this regret to make it more money.

When Molly-Mae stated the app would encourage “girls to think ‘this is actually in really great condition I don't need to chuck it away, why not encourage someone else to buy it’”, she never once questioned why shoppers aren’t already rewearing their clothes. The fact that customers would even think to bin their PLT outfits says a lot about their disposability.

It also says a lot about how we value our clothes. While Molly-Mae claims that “our people that produce and work on our garments don’t work day-in day-out on these pieces for them to be throwaway fashion”, the brand’s continuous sales tell a different story. How can you possibly recuperate money on an item that is deemed worthless by the same company that offered a 100% Black Friday sale?

As Tolmeia puts it, the move is merely “PR offsetting”. Amid news of protest, insensitive comments and labour scandals, PLT will do anything to save its reputation. Here, press coverage, website traffic and profit go hand-in-hand. PrettyLittleThing’s resale app hopes to generate all three.

Regardless if the resale app succeeds in altering consumer behaviour, it will never offset the environmental impact of production. Without committing to degrowth, all the app will do is help customers clear out their wardrobes for more PLT clothes. Ironically, the secondhand platform will likely encourage customers to buy more firsthand items. It’s business as usual as PrettyLittleThing HQ.

Caught Green Handed: Shein

The Wish of the fashion world, Shein is shrouded in secrecy and scandal. Shoppers can’t guarantee when their parcel will arrive and can only hope their order will bare some resemblance to online images. The quality of the clothing is pretty hit or miss.

Even less is known about who makes these clothes. An investigative report by Reuters found that Shein had failed to fully disclose the working conditions throughout its supply chain, as required by the UK’s Modern Slavery Act. What’s more, the company’s website falsely claimed that “conditions in the factories it uses were certified by international labour standards bodies.”

Shein’s murky social and environmental stance is widely known, but this hasn’t stopped the brand from disrupting the US Market. Last June, Shein became the largest fast fashion retailer in the US by sales, overtaking H&M, Zara and Forever 21.

Why? Because Shein shamelessly rips off indie designers, exploits tax loopholes and dropships ridiculously cheap clothes. The average unit price for a Shein product is just $7.90 - a price tag matched only by Primark and Forever 21. Which means $500 Shein sized baskets aren’t all that uncommon; #Sheinhaul has 4.5 billion views on TikTok alone.

Shein is as opaque as they come, but where it really stands out from other brands is in its transparent attitude to sustainability. While rivals spend millions on greenwashing, Shein has taken pride in its ultra fast fashion model and regularly boasted about its unmatched ability to stock thousands of new styles daily.

Until now. Taking notes from its competitors, Shein has suddenly committed itself to sustainability. In a hard to find campaign page on its US site, Shein lists its “sustainable practices for a healthier planet.” Surprise, surprise, they’re a load of bollocks. Let’s unpack what is being said here.

“While others go big, we go small. That means we only produce 50-100 new pieces per new product [emphasis theirs] to ensure that no raw materials are wasted. Only when we confirm that a style is in high demand, do we implement large scale production.”

Slow manufacturing and small production batches sounds too good to be true and that’s because they are. 50 items per style sounds pretty minimal until you realise just how many styles are being simultaneously released. In an interview given to Forbes in May 2020, CMO Molly Miao revealed Shein drops 700 to 1,000 new items a day on the site. This figure has since risen dramatically.

Between 17th February and 23rd February this year, 40,348 new styles were released on the US site, averaging at 5,764 drops a day. If we take the conservative estimate that 50 units per style were ordered, that’s 2,017,400 items of clothing ready to be shipped in just one week. Of course, the real figure is a lot higher, as up to 100 units of each style were ordered, and then the bestsellers are restocked at a “large scale”. This supply and demand justification of mass production is scapegoating, given that Shein is stocking millions of garments every 7 days, somewhat independent of buying behaviour.

It boils down to this: you can never dream of becoming a remotely sustainable brand which such a rapid and gross turnover of product. Products that are sold on a site that encourages you to check back regularly, buy constantly and wear once. Shein isn’t any better than other fast fashion brands and it certainly isn’t “small”.

“When selecting materials, we do our best to source recycled fabric, such as recycled polyester, a non-virgin fibre that has little impact on the environment and reduces damage to the original material.”

When you’re a multi-billion dollar brand, you have to do more than try your best. Shein doesn’t provide any evidence for its claim that (presumably post-consumer?) recycled polyester has “little impact on the environment”. While it may fare better than its virgin counterpart in the manufacturing process, recycled plastics still shed thousands of microfibres and do not biodegrade. Plus, recycled polyester cannot be recycled further after use, so I wouldn’t say the impact here is “little”.

“Meetings are kept to a minimum to conserve paper and electricity, and our power and water automatically switch off when not in use.”

I rolled my eyes at this one. How, in the advanced technological world of 2022, are we patting ourselves on the back for conserving power?! The lights in my primary school classroom turned off when it was vacant ffs!

Instead of banging on about paper, Shein should focus on the sprawling mass of plastic it produces. And those meetings they keep to a minimum? That will be the sustainability strategy meetings I’m sure.

“We have a strict no animal policy. That means we only use faux fur/leather and we prohibit animal testing on our products.”

Commendable, right?! Not really. Last month, we looked at how “vegan leather” and faux fur is usually just plastic. Non-biodegradable, often toxic, far less durable plastic.

“We’ve implemented an incentivising Recycling Program that encourages customers to bring in unwanted clothes to our pop-up and college campus events in exchange for Shein gift cards.”

H&M was the first fast fashion retailer to perfect the good ol’ take-back scheme, which invites customers to donate old clothes to be “recycled” in exchange for a gift card. I say “recycled” because you can’t guarantee where the clothes will end up. Some garments will be repurposed into new consumer goods, some will be down-cycled into industry materials and tons more will be sold on, often overseas, burdening its recipients. There’s also the argument that exchanging clothes for gift cards incentivises shoppers to keep buying more, with the feel-good guarantee they can later bring them back to be recycled. Megan Doyle has written a great review of the “far from perfect” take-back scheme.

“The donated clothes are then refurbished and given to various charities to help people in need.”

This is extremely vague. How are clothes refurbished and is this different to being recycled? Are they repaired, altered, upcycled or simply thrown in the washing machine? It would also be good to know who these charities are and how they process this clothing.

“Our products / Our planet.”

A slash is commonly used to signify the word “or”. Shein has given itself an ultimatum: do we protect our products or our planet? My money’s on the former.

Did you enjoy this post? Please share it with a friend, subscribe or gift me a virtual cuppa. I’ll never put my content behind a paywall so Ko-fi is a small and optional way to support my work 🫶