Caught Green Handed is a monthly newsletter interrogating fashion, capitalism and greenwashing. If you like what you read, subscribe to get the next one sent straight to your inbox 🫶

“Can we just enjoy things?!” - those five words were the involuntary soundtrack of my summer.

It all started with the Euros or more specifically its sponsors. Instead of following the game, I found my gaze repeatedly interrupted by jarring pitchside advertisements as Adidas, Coca Cola and Booking.com all competed for my attention. Momentarily relief came in the form of a half time break. Just as my annoyance started to subside, David Beckham appeared on the screen promoting Ali Express tat.

The Paris Olympics offered another sporting-arena-turned-corporate-playground, a “shared space for brands to conquer” as Alec Leach puts it. The committee’s ambitious goal to halve the usual carbon footprint of the games was at odds with its long list of polluting partners - Coca Cola, Toyota, Visa, EDF Energy, Airbnb and Samsung among them.

While Lululemon dressed team Canada in head-to-toe synthetics, LVMH - the same luxury retailer facing sweatshop allegations - plastered the city in its image, dressing athletes, celebrities and giant billboards alike.

By the time I arrived at Brighton Pride parade, I knew what to expect. With my “I’m on pinkwash watch” sign at the ready, I looked on as Coca Cola (are you noticing a theme here?), American Express and Tesco’s portable advertisements eclipsed the floats of local community groups and the emergency services in size, light and sound systems and what sometimes felt like crowd cheers. Skittles ads followed me all weekend displayed on the back of bikes and on the side of parked vans with the engine still running. The anti-establishment origins of Pride were lost to rainbow capitalism.

And who could forget brat summer. Call me naïve but brat mania felt less manufactured than the Barbie summer of the previous year. Rejecting one single visual aesthetic, brat is (was?) more of a mindset than a definable list of clothes you must own. It’s open to interpretation. Brat really is what you make it, leaving Business of Fashion to question if brands could profit from the cultural moment of the summer.

That of course didn’t stop them from trying. Vogue made commission from its “essential” brat girl summer starter pack. Zara and H&M recoloured their Instagram logos. airBaltic rebranded its TikTok account to airBrat. In a brilliant post, The Climate Propagandist analyses how these brands used “bratwashing” as a “shortcut to win back younger audiences”. And that’s exactly what this is: a shortcut, an ill substitute for culture that reeks of inauthenticity.

After three months of style guides, apple dances and AI-generated text posts, brat summer was declared forever over, a premature ending many fans protested. Sure, the sunshine had gone but the essence of brat wasn’t something you could easily put back on a leash. It had taken on a new, unexpected life of its own.

A surprising LFW performance for H&M’s A/W campaign soon filled the void. The antithesis of brat, this collaboration added a bitter corporate taste to something that had so far resisted associations with any one brand, let alone the poster child of big fashion. I’m personally with Chappell Roan on this one: “fuck H&M”.

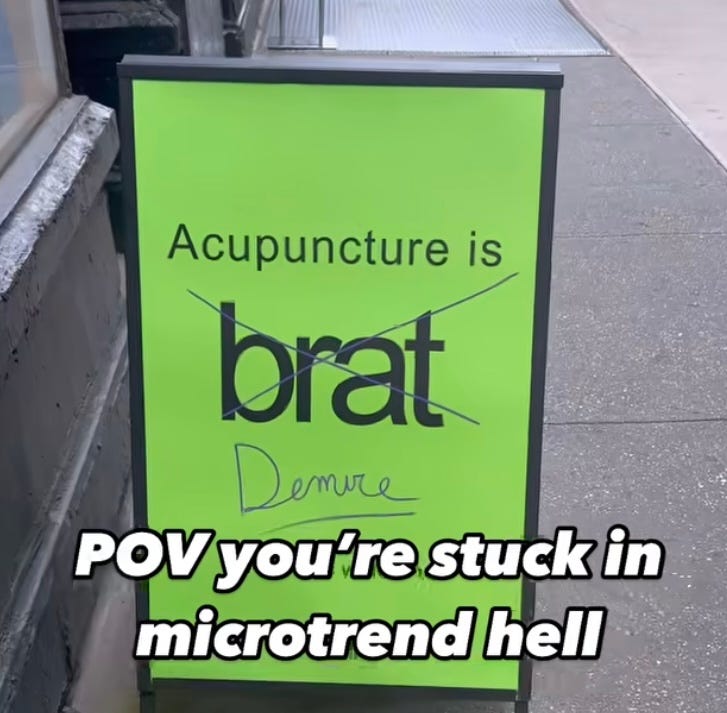

Next came demure, a viral catchphrase that gifted the creator and overnight sensation Jools Lebron enough money to pay for her transition. It wasn’t long before brands jumped on the social media bandwagon and somebody else tried to trademark her saying. But it was the speed in which demure went from cool to outdated that really gave me whiplash. Fast fashion, fast homeware, fast language. Now even our vocabulary has a short shelf life, as this reel satirises.

Somewhere between brat and demure, underconsumption had a -core added at the end of it. Deinfluencing’s younger sister, the trend is another manifestation of growing resentment against influencer culture, this time defined by the normalisation of repair and reuse. Although the original meaning was lost on some creators who instead filmed themselves throwing out perfectly usable items.

The deinfluencing trend similarly started out as a montage of anti-hauls before it evolved into a sales tactic. The hashtag soon became inundated with videos recommending one product over another, many of them conveniently linked on TikTok shop. Another tragic victim of the family curse.

The commercialisation of these trends is part of a broader phenomenon where subcultures get swept up into marketable microtrends. As Katie Robinson laments, we’re sold personalities like they’re costumes, something to dress up in then discard when the next best thing comes along. We’re unwilling or unable to decouple our interests and identity from our purchasing habits. The constant impulse to reinvent ourselves is palpable. It’s exhausting.

Of course what I am describing isn’t new. Capitalism, by design, is a cannibalising force that feasts on any element of culture it can profit from. What was novel was my inability to switch off from it, to retrain my obsessive eye to look away for just a second and to take my friends up on their offer to “just take a day off”.

My summer was defined by every shade of washing - sportswashing, pinkwashing, greenwashing, even bloody bratwashing - and it momentarily robbed me of my ability to enjoy things. I’m now trying my hardest to steal it back.

Caught Green Handed: Primark’s durability framework

“Worth every penny”, “buy cheap, buy twice”, “get your money’s worth” - we’ve been hardwired to believe that cost is a foolproof measure of quality. But a new-ish report funded by Primark proves that price isn’t an indicator of clothing durability. Sometimes you don’t get what you paid for.

The study tested 65 items of clothing priced between £5 and £150 against specific wash and performance standards. It found that price doesn’t correlate with durability, with “some of the more affordable clothing perform[ing] just as well as, or even better than, more expensive ones”. This doesn’t come as a huge shock, given that overlapping supply chains and scandals have left many to question how different fast fashion and luxury really are.

When it was first published last July, many of us questioned the motive behind the report. We now have our answer: the study, alongside input from WRAP, informed Primark’s durability framework which aims “to set the bar for how retailers can extend the life of their clothing“. The move follows a concerted effort by Primark to champion durability as a core sustainability metric but this emphasis is completely misplaced - here’s why.

Just because something can technically last for centuries doesn’t mean it should

Let’s get the obvious out of the way: of course synthetics are durable. Anything that takes hundreds of years to decompose fits this criteria. Durable derives from the Latin verb durare meaning “to last”, a fitting reminder that sprawling mountains of polyester clothing will outlast us all.

Interestingly or maybe concerningly, the original study doesn’t disclose the fabric composition of the garments that were tested. We’re now told it was cotton. Both the initial omission and the choice to test cotton is intriguing given a massive chunk of Primark’s clothes are made from synthetics.

While it refuses to disclose the exact amount of synthetics it uses, Primark recently informed Changing Markets of its plans to increase its use of synthetics in the future - a “justifiable” choice if your main sustainability benchmark is durability.

Emotional durability determines the true lifespan of a garment

Primark commissioned the research because it “wanted to show that all garments deserve to be cared for equally, regardless of their price”. Which is a nice sentiment if it wasn’t said by a brand that helped lead the fast fashion charge that has warped our sense of value and underpinned a culture of mindless consumerism.

Recognising the tension between brands’ sustainability strategies and their growing dependency on synthetics, The Plastic Elephant in the Room report argues that durability doesn’t automatically increase the lifetime of a garment or lead to fewer purchases because clothes are rarely acquired as replacements for worn-out items.

Emotional durability more accurately determines how long a garment will be worn and cared for. Primark hopes to inspire its customers to love their purchases for longer through education, repair workshops and popularising the perception that price doesn’t equal durability. An admirable feat for sure, but how easy is it to reverse decades of messaging that has led people to look after their clothes differently depending on how much they paid? How can you ever expect your customers to value clothes that cost the same as a meal deal?

People shouldn’t have to endure shit working conditions for the sake of long lasting clothes

Who are Primark’s clothes really durable for? Is it the customer whose purchase can now sustain 45 washes or the brand who benefits from a boost in trust and revenue? Is it the suppliers who are expected to deliver on brands’ sustainability targets for the same pay and unequal power dynamic? What about the garment workers who are struggling to survive on poverty wages?

I don’t care if a t-shirt is “durable” if it was made in exploitative conditions. The human capacity to withstand pressure, change and damage is just as important as the Earth’s ability to withstand the needless overproduction of so-called durable clothes.

The Bottom Line

Important things to read & do

Ahead of Black Friday, the OR Foundation is calling on brands of all sizes to Speak Volumes. Learn more and support the campaign here

As if there wasn’t enough digital ad screens in Bristol, Exterion Media has submitted planning applications for three more “communication hubs”. Help block these applications by leaving an objection

“Circular fashion isn’t launching a resale app, a repair scheme or a rental option as an alternative to just making less shit” - I teach big fashion a thing or two about circularity in this reel

Some of the links in this newsletter are behind a paywall. This is my favourite tool for bypassing them

The CMA has issued tailored anti-greenwashing guidance for the fashion industry and warned 17 brands to review their green claims

My wonderful colleagues at Estethica - Orsola de Castro, Roxanne Houshmand-Howell and Tamsin Blanchard - have started their own Substack decoding the sustainable fashion oxymoron

After a string of labour rights scandals, Better Cotton is transitioning into a certification scheme. Samantha Taylor questions whether the BCI label was “one of the biggest scams in fashion”

Italy’s antitrust agency is investigating whether Shein’s “evoluSHEIN” collection amounts to greenwashing (spoiler alert: it does)

A new study adds credence to the polluters pay principle, revealing that we underestimate the personal carbon footprint of the richest while overstating the contribution of the poorest